In the first two sections of our opioid education series we discussed the different classifications of pain and how to best provide safe and efficient opioid and nonopioid pain management. In this third and final section, we will focus primarily on ways you can engage and educate patients about their pain to optimize safe and effective multimodal treatment plans.1 Providers should utilize patient-centered strategies to help patients develop a greater understanding of their underlying disease process and pain triggers and educate them on how to seek appropriate professional care.

In the first two sections of our opioid education series we discussed the different classifications of pain and how to best provide safe and efficient opioid and nonopioid pain management. In this third and final section, we will focus primarily on ways you can engage and educate patients about their pain to optimize safe and effective multimodal treatment plans.1 Providers should utilize patient-centered strategies to help patients develop a greater understanding of their underlying disease process and pain triggers and educate them on how to seek appropriate professional care.

Patient engagement may include discussions between the patient and provider about treatment goals, expectations and risks, signs of dependence, and documented contracts or agreements outlining the responsibilities of both participants in the treatment process if opioids are prescribed.2 Goals should focus on improvement in pain and function and should be realistic, specific, and measurable.3,4 Patients should receive information about pain management options and potential treatment outcomes, including the benefits and risks of non-opioid pharmacotherapy, nonpharmacological therapies, and opioid therapy. Providers should assist patients with the evaluation of pain management options based on the patient’s values and preferences to enable a shared decision between the patient and physician on initiation of opioid therapy.5 A written, formalized contract can help establish and document a common understanding between the patient and provider.6 To minimize the risk of opioid use disorder (OUD) and overdose, patients should also be educated about the signs and symptoms of opioid dependence and withdrawal; and safe storage and disposal of medication.

Medication Storage and Disposal

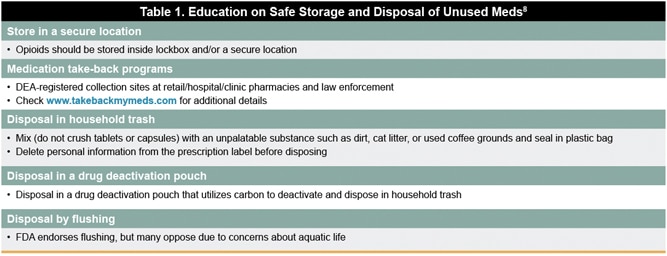

Safe storage and disposal of opioids is essential to minimize diversion. Medications should be stored in their original packaging inside a locked cabinet, a  lockbox, or other secure location.7 The FDA recommends consumers follow instructions for safe disposal provided on the medication label.8 All expired and unused medications should be removed from the home as quickly as possible to reduce the chance of misuse and diversion. If there are no disposal instructions on the label, the FDA endorses three options for discarding unused or expired medications:

lockbox, or other secure location.7 The FDA recommends consumers follow instructions for safe disposal provided on the medication label.8 All expired and unused medications should be removed from the home as quickly as possible to reduce the chance of misuse and diversion. If there are no disposal instructions on the label, the FDA endorses three options for discarding unused or expired medications:

(1) Medication take-back programs: Two types of medication take-back programs are available: permanent DEA-registered collection sites including select retail/hospital/clinic pharmacies and law enforcement facilities, and periodic events such as national prescription drug take-back events. Patients and providers can use the website www.takebackmymeds.com for the nearest location.

(2) Disposal in household trash: To dispose medication in household trash, mix (do not crush tablets or capsules) with an unpalatable substance such as dirt, cat litter, or used coffee grounds. Seal the mixture in a plastic bag and throw in the trash. Delete personal information from the prescription label before disposing. New technologies are available that utilize carbon to deactivate the medication in a pouch.

(3) Flushing certain medications: A small number of prescription drug labels instruct patients to immediately flush unneeded medication down the toilet when take-back programs are not readily available. Many communities oppose flushing because of risk to aquatic life. Due to the risk to humans, including death from accidental exposure, flushing the medication is necessary in the absence of a take-back program.

Naloxone is an FDA-approved medication that rapidly reverses the effects of opioids, such as respiratory depression, which is the cause of death in the majority of overdoses.9,10 Wider naloxone administration and education has been identified as a priority area in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Opioid Misuse Strategy.10 In December 2018, the Department of Health and Human Services released a recommendation for co-prescribing naloxone with opioids to patients at high risk of opioid overdose.11 In 2014, the FDA approved a subcutaneous/intramuscular autoinjector form that could be administered by an individual. In 2017, they approved a nasal spray form of naloxone. Allison L. Pitt and her Stanford colleagues point out that none of the current treatment and policy proposals can substantially reduce opioid-induced deaths in the long term, but of the current interventions, naloxone could have the most impact. Studies have shown the public health benefits of community-based overdose education and naloxone distribution programs that provide naloxone and train at-risk individuals and their friends, family members or caregivers on overdose prevention and response.12 Such programs have led to significant reductions in opioid-related overdose death rates.13-15

Medication-Assisted Treatment

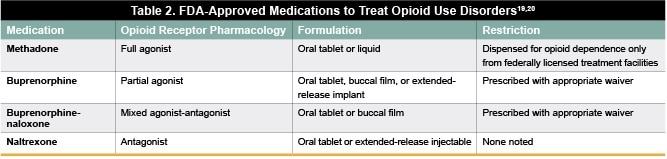

Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) involves the use of medications combined with behavioral therapies for the treatment of substance use disorders,  including OUDs. Pharmacotherapies used to treat OUD include methadone, buprenorphine, buprenorphine-naloxone, and naltrexone (Table 2). Studies have shown that MAT is effective for the treatment of OUDs, with success rates ranging from 50% to 66% as measured by mortality reduction and opioid use suppression.16,17 In one study, patients who continued to receive MAT at 18 months were more than twice as likely to report avoidance of non-medical use of opioids compared with those who were not receiving MAT (80% vs 36.6%).18

including OUDs. Pharmacotherapies used to treat OUD include methadone, buprenorphine, buprenorphine-naloxone, and naltrexone (Table 2). Studies have shown that MAT is effective for the treatment of OUDs, with success rates ranging from 50% to 66% as measured by mortality reduction and opioid use suppression.16,17 In one study, patients who continued to receive MAT at 18 months were more than twice as likely to report avoidance of non-medical use of opioids compared with those who were not receiving MAT (80% vs 36.6%).18

Buprenorphine Prescribing

Under the Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000, healthcare providers must qualify for and obtain a waiver to prescribe buprenorphine for OUD (Table  3).21 Despite only requiring eight hours of training to receive a prescribing waiver, just 4% (or 37,448) of all active physicians in the United States have applied for a waiver.22,23 A study by Andilla et al found that 60% of rural counties lacked a single physician authorized to prescribe buprenorphine, demonstrating current barriers to treatment access for patients, particularly in rural and underserved areas.24 Several barriers to buprenorphine treatment have been identified, including federal limits on the number of patients a physician may treat with buprenorphine; federal limits on nurse practitioners’ and physician assistants’ prescribing; inadequate integration of buprenorphine into primary care treatment; and stigma against maintenance treatment for opioid addiction.25 Addressing these barriers to increase the number of prescribers approved to prescribe buprenorphine will expand access to treatment and improve outcomes for patients with OUD.

3).21 Despite only requiring eight hours of training to receive a prescribing waiver, just 4% (or 37,448) of all active physicians in the United States have applied for a waiver.22,23 A study by Andilla et al found that 60% of rural counties lacked a single physician authorized to prescribe buprenorphine, demonstrating current barriers to treatment access for patients, particularly in rural and underserved areas.24 Several barriers to buprenorphine treatment have been identified, including federal limits on the number of patients a physician may treat with buprenorphine; federal limits on nurse practitioners’ and physician assistants’ prescribing; inadequate integration of buprenorphine into primary care treatment; and stigma against maintenance treatment for opioid addiction.25 Addressing these barriers to increase the number of prescribers approved to prescribe buprenorphine will expand access to treatment and improve outcomes for patients with OUD.

Destigmatizing Language

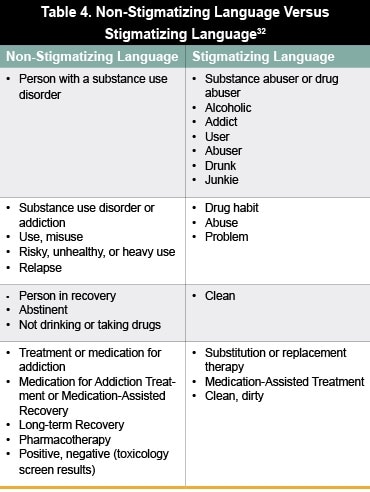

Focus on supply has a limited efficacy27 and can be counterproductive in reinforcing shame and stigma. The public perception of individuals who use  opioids is overwhelmingly negative, leading to an aversion to confront potential addiction.28-30 High levels of stigma associated with opioid use are common not only in the general public but also found among key groups involved in responding to the opioid epidemic, including first responders, public safety officers, and healthcare providers.30 Stigma is a key barrier that prevents patients from seeking care.32 As a consequence, only 10% of individuals with substance use disorder get treatment;33 women, communities of color, and residents of rural areas often face additional barriers to accessing services and are even less likely to receive treatment.34 Thus, it is important that providers aim to reduce stigma and minimize barriers to treatment. To this end, a nationwide public education campaign is being promoted to combat the opioid crisis and reduce this stigma by emphasizing that addiction is not a moral failing, but rather a chronic brain disease with evidence-based treatment options.33,12 A report published by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and the Clinton Foundation recommends to combat stigma by avoiding stigmatizing language and including information about treatment barriers and treatment effectiveness when communicating with the public about opioid-use disorders (Table 3).25,32 This includes replacing dehumanizing terms (eg, “substance abuser,” “addict,” or “junkie”) with non-stigmatizing language (eg, “person with a substance use disorder”).

opioids is overwhelmingly negative, leading to an aversion to confront potential addiction.28-30 High levels of stigma associated with opioid use are common not only in the general public but also found among key groups involved in responding to the opioid epidemic, including first responders, public safety officers, and healthcare providers.30 Stigma is a key barrier that prevents patients from seeking care.32 As a consequence, only 10% of individuals with substance use disorder get treatment;33 women, communities of color, and residents of rural areas often face additional barriers to accessing services and are even less likely to receive treatment.34 Thus, it is important that providers aim to reduce stigma and minimize barriers to treatment. To this end, a nationwide public education campaign is being promoted to combat the opioid crisis and reduce this stigma by emphasizing that addiction is not a moral failing, but rather a chronic brain disease with evidence-based treatment options.33,12 A report published by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and the Clinton Foundation recommends to combat stigma by avoiding stigmatizing language and including information about treatment barriers and treatment effectiveness when communicating with the public about opioid-use disorders (Table 3).25,32 This includes replacing dehumanizing terms (eg, “substance abuser,” “addict,” or “junkie”) with non-stigmatizing language (eg, “person with a substance use disorder”).

High levels of social stigma have been linked to greater support for punitive policies and lower support for public health-oriented policies that affect individuals with OUDs.30 Nonetheless, criminalization as a response to the opioid crisis has been recognized as ineffective at reducing rates of opioid use and overdose.34 There is a need to shift the focus on criminalizing OUD to expanding evidence-based treatment programs that will improve clinical outcomes. Many states have embarked upon novel programs to address the opioid crisis through evidence-based approaches—two examples of such programs are explored here.35-37

West Virginia University Comprehensive Opioid Addiction Treatment Clinic35,36

Started in 2004, the COAT (Comprehensive Opioid Addiction Treatment) clinic at West Virginia University is a highly structured and efficient group-based approach to opioid addiction treatment. This approach involves extensive use of shared medical visits, with on‐site group therapy and case management. Random drug screening, routine medication monitoring, and buprenorphine-naloxone administration are used for medical management. Co-occurring disorders are managed separately by a multidisciplinary team. Patients in beginner and intermediate groups must attend four outside support meetings every week and become eligible for advanced (monthly) groups after 1 year of sobriety. The COAT model has been expanded to four additional locations across West Virginia, which serve as Centers of Excellence providing state-wide support to office-based physicians through tele-health programs. The West Virginia University COAT model illustrates that medication alone is not sufficient to treat opioid addiction and the integration of group therapy and psycho-education with medical management can improve quality of life and decrease mortality.

Massachusetts Police-Led Addiction Treatment Referral Program37

In the town of Gloucester, MA, police officers were faced with ever increasing rates of overdose deaths and determined that action was necessary. The Gloucester Police Department responded by developing a novel Angel Program to address the needs, stigma, and fears in their community. The voluntary, no-arrest program offers direct referrals for drug detoxification or rehabilitation services to residents. Through the program, police officers collect demographic information, identify a facility, and secure placement for each individual. They provide transportation to the facility and assign a volunteer Samaritan for emotional support if placement is expected to take more than a few hours. In the first year of the program (June 2015 to May 2016), 376 different persons presented to the police for assistance 429 times. During a one-year period, the direct referral to treatment of 94.5% exceeds rates reported for hospital-based initiatives. This model has been adopted by 153 other police departments in 28 states. Awareness and education about such best practices can lead to expansion of such programs in additional communities.

Faculty Panel Insights

The overall consensus among the faculty panel was that a collaborative patient-centered approach is needed to guide optimal pain management.  Providers need to educate patients about their pain in order to optimize safe and effective multidisciplinary treatment plans. The faculty panel highlighted the importance of understanding the complex biopsychosocial aspects of pain. Best practices include the careful integration of multimodal approaches including non-pharmacologic and non-opioid interventions. Providers need to understand and manage patient expectations. Pharmacovigilance is needed to apply an evidence-based approach to chronic pain management and improve prescribing practices. More education is needed to reduce stigma and increase treatment access. Concepts from successful novel programs should be integrated into clinical practice.

Providers need to educate patients about their pain in order to optimize safe and effective multidisciplinary treatment plans. The faculty panel highlighted the importance of understanding the complex biopsychosocial aspects of pain. Best practices include the careful integration of multimodal approaches including non-pharmacologic and non-opioid interventions. Providers need to understand and manage patient expectations. Pharmacovigilance is needed to apply an evidence-based approach to chronic pain management and improve prescribing practices. More education is needed to reduce stigma and increase treatment access. Concepts from successful novel programs should be integrated into clinical practice.

Please be sure to check out part 1 and part 2 of this series, entitled Addressing the Opioid Epidemic: Reducing the Burden of Pain in a Changing Treatment Statement and Addressing the Opioid Epidemic: Principles of Communication and Addressing Patient Needs for valuable expert insights on the pathophysiology of pain, safe pain management approaches, and how to reduce the risk of addiction when prescribing opioids.

To obtain credit for this activity, please click here.

References

- Pain Management Best Practices Inter-Agency Task Force – Draft Report on Pain Management Best Practices: Updates, Gaps, Inconsistencies, and Recommendations. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/2018-12-draft-report-on-updates-gaps-inconsistencies-recommendations/index.html. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Pain Management Task Force. Environmental Scan Report. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/meetings/2018-05-30/environmental-scan-report/index.html. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Hooten M, Thorson D, Bianco J, et al. Pain: assessment, non-opioid treatment approaches and opioid management. August 2017. Available from: https://www.icsi.org/guidelines__more/catalog_guidelines_and_more/catalog_guidelines/catalog_neurological_guidelines/pain/. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Manchikanti L, Abdi S, Atluri S, et al. American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines for responsible opioid prescribing in chronic non-cancer pain: part 2—guidance. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):S67-116.

- Manchikanti L, Kaye AM, Knezevic NN, et al. Responsible, safe, and effective prescription of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain: American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians (ASIPP) guidelines. Pain Physician. 2017;20(2S):S3–S92.

- Albrecht, JS, Khokhar B, Pradel F, et al. Perceptions of patient provider agreements. Journal of Pharmaceutical Health Services Research: An Official Journal of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain. 2015;6(3):139–144.

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Pain management and opioid abuse: a public health concern. July 2012. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/pain_management/opioid-abuse-position-paper.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Disposal of Unused Medicines: What You Should Know. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/BuyingUsingMedicineSafely/EnsuringSafeUseofMedicine/SafeDisposalofMedicines/ucm186187.htm. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Chang KL, Fillingim R, Hurley RW, Schmidt S. Chronic Pain Management. FP Essentials™, Edition No. 432. Leawood, KS: American Academy of Family Physicians; May 2015.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). Opioid Misuse Strategy 2016. January 5, 2017. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/outreach-and-education/outreach/partnerships/downloads/cms-opioid-misuse-strategy-2016.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Department of Health and Human Services. Naloxone: The Opioid Reversal Drug that Saves Lives. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/opioids/sites/default/files/2018-12/naloxone-coprescribing-guidance.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019

- Alexander GC, Frattaroli S, Gielen AC, eds. The Prescription Opioid Epidemic: An Evidence-Based Approach. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD: 2015.

- Albert S, Brason F, Sanford C, Dasgupta N, Graham J, Lovette B. Project Lazarus: community-based overdose prevention in rural North Carolina. Pain Med. 2011;12:S77-S85.

- Brason F, Roe C, Dasgupta N. Project Lazarus: An innovative community response to prescription drug overdose. N C Med J. 2013;74:259-261.

- Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8:153-163.

- Sarlin E. Long-Term Follow-Up of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Addiction to Pain Relievers Yields “Cause for Optimism.” November 30, 2015. Available at: https://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/nida-notes/2015/11/long-term-follow-up-medication-assisted-treatment-addiction-to-pain-relievers-yields-cause-optimism. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Pierce M, Bird SM, Hickman M, et al. Impact of treatment for opioid dependence on fatal drug-related poisoning: a national cohort study in England. Addiction. 2016;111(2):298-308.

- Potter JS, Dreifuss JA, Marino EN, et al. The multisite prescription opioid addiction treatment study: 18-month outcomes. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;(48)1:62-69.

- VA South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Pocket guide for clinicians for management of chronic pain. January 2017. Available at: https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/pain-management-pocket-guide.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Moran GE, Snyder CM, Noftsinger RF, et al. Implementing medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder in rural primary care: environmental scan, volume 1. (Prepared by Westat under Contract Number HHSP 233201500026I, Task Order No. HHSP23337003T). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; October 2017. Publication No. 17(18)-0050-EF.

- Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 (DATA 2000). Title XXXV, Section 3502, of the Children’s Health Act of 2000. Public Law 106-310-106th Congress.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). Physician and program data. SAMHSA Website.

- Henry J, Kaiser Family Foundation. State health facts: total professionally active physicians. Kaiser Family Foundation Website. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-active-physicians. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Andrilla CHA, Coulthard C, Larson EH. Barriers rural physicians face prescribing buprenorphine for opioid use disorder. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):359-362.

- Alexander GC, Frattaroli S, Gielen AC, eds. The opioid epidemic: from evidence to impact. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2017.

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). How to obtain a waiver to treat opioid use disorder with buprenorphine. November 21, 2018. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/journals/fpm/blogs/inpractice/entry/opioid_use_disorder.html?cmpid=em_FPM_20181128. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Srivastava AB, Gold MS. Beyond supply: how we must tackle the opioid epidemic. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(3):269-272.

- Barry CL, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Gollust SE, et al. Understanding Americans’ views on opioid pain reliever abuse. Addiction. 2016;111(1):85-93.

- McGinty EE, Goldman HH, Pescosolido B, Barry CL. Portraying mental illness and drug addiction as treatable health conditions: effects of a randomized experiment on stigma and discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2015;126:73-85.

- Kennedy-Hendricks A, Barry CL, Gollust SE, Ensminger ME, Chisolm MS, McGinty EE. Social stigma toward persons with prescription opioid use disorder: associations with public support for punitive and public health-oriented policies. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68(5):462-469.

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, et al. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131:23-35.

- Boston Medical Center. Words Matter. Available at: https://www.bmc.org/sites/default/files/Patient_Care/Specialty_Care/Addiction-Medicine/LANDING/files/Words-Matter-Pledge.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. 2017. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Final_Report_Draft_11-15-2017.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Drug Policy Alliance. A Public Health and Safety Approach to Problematic Opioid Use and Overdose. Available at: https://www.drugpolicy.org/sites/default/files/Opioid_Response_Plan_041817.pdf. Accessed January 29, 2019.

- West Virginia University (WVU). Comprehensive Opioid Addiction Treatment provides group-based treatment program using medication assisted therapy (MAT). Available at: https://medicine.hsc.wvu.edu/bmed/addiction-services/comprehensive-opioid-addiction-treatment-coat/. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Schreyer N. WVU Medicine opioid addiction treatment clinic a model for the state. December 28, 2016. Available at: https://www.wvgazettemail.com/news/education/wvu-medicine-opioid-addiction-treatment-clinic-a-model-for-the/article_6f63ff3a-09cb-574e-aa1a-f0e8728606d4.html. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Schiff DM, Drainoni ML, Bair-Merritt M, Weinstein Z, Rosenbloom D. A police-led addiction treatment referral program in Massachusetts. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(25):2502-2503.

- Alford DP. Opioid prescribing for chronic pain–achieving the right balance through education. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):301-303.