In December 2018, the Opioid Healthcare Provider/Advocacy Working Group convened for a two-day advisory board meeting with representatives from the primary care, pain management, oral surgery, orthopedic surgery, addiction, and physician assistant healthcare provider community, and the DEA Educational Foundation. The purpose of this meeting was to address the opioid epidemic and develop actionable steps to promote appropriate prescribing for individuals with acute and chronic pain to curb the impact of the growing crisis facing our communities.

The data and trends illustrating the impact of opioids on the United States are staggering. From July 2016 through September 2017, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported:1

- A 30% increase in overdoses among men and a 24% increase among women.

- All ages were affected—a 31% increase among individuals aged 25 to 34 years, a 36% increase among those aged 35 to 54 years, and a 32% increase among those over 55.

- The Midwest experienced an astounding 70% increase in opioid overdoses.

- From rural to urban settings, communities witnessed the growing and deadly impact of opioids.

The panel of faculty experts gathered to provide insight on the challenges, consequences, and opportunities for the development of education to help meet the pain management needs of patients amid the ongoing opioid concerns of addiction and diversion. Their experience and insights will be reflected in this 3-part web series.

Understanding the Pain Landscape

Fueled by the rise in opioid misuse, the United States is currently facing the worst drug overdose crisis in our nation’s history. The United States has the highest rate of opioid use in the world, with per capita consumption exceeding the next country, Canada, by more than 50%.2 In 2017, the United States had 70,237 drug overdose deaths, of which 47,600 (67.8%) were from opioid overdoses. Between 1999 and 2015, it was estimated that the annual number of opioid-related deaths quadrupled in the United States.3 The risks brought on our communities by the opioid epidemic are devastating—addiction, overdose, progression to heroin, neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome, and increased incidence of infectious disease transmission (eg, HIV and hepatitis C) through injection drug use of prescription or illicit opioids.4,5

Changing current trends in opioid use cannot be accomplished by policies alone or strategies that are applied among only healthcare providers, government agencies, associations, or law enforcement. Importantly, it requires a coordinated public health approach that incorporates all of these groups, led by the best evidence, working in tandem—and with patients—to achieve the goals that will reverse the current destructive trends.

The growing burden caused by opioid use disorder (OUD) in our communities and the role of all stakeholders in addressing the opioid epidemic are highlighted in a September 2018 report by McKinsey and Company, which suggests that the opioid crisis may worsen, and that bolder and broader actions must be taken.6 Themes fall under prevention-focused (eg, improve prescribing practices, collaborate with law enforcement, address risk factors), treatment-focused (eg, increase availability of naloxone, expand capacity of medication-assisted treatment [MAT]), and how to control foundational enablers (eg, promote coordinated opioid strategy, leverage analytics to support and improve interventions).

The role of the US Drug Enforcement Administration

The US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) enforces the provisions of the Controlled Substances Act, which classifies drugs into one of five schedules based on their medical utility as well as the potential for abuse, misuse, and physical and psychological dependence.7 Over the past decade, the rise in prescription drug abuse has led to increased law enforcement scrutiny of healthcare providers who must register for a DEA license to prescribe controlled substances. The regulation of prescription controlled substances has been described as a volatile “clash” of cultures between law enforcement and medicine.8 The former aims to improve public safety through criminalizing illegal drug activity; the latter interacts at the patient level with the goal of improving individual health and well-being through a continuing relationship. 8

When used appropriately, prescription opioids are a powerful and effective tool in pain management.9 However, many primary care providers (PCPs) report concerns about opioid prescribing and insufficient pain management training. Results of a survey by Jamison et al showed that 89% of PCPs were concerned about misuse, 84% were stressed about managing chronic pain, and 54% reported that they did not feel sufficiently trained and lacked confidence in prescribing opioids.10 With the exception of federal prescribers who are required to be trained, it is estimated that fewer than one-fifth of the over one million prescribers licensed to prescribe controlled substances have training on how to prescribe opioids safely.11

Cross collaboration

The DEA should partner with the prescribing community by engaging in a more open dialogue to take advantage of opportunities to decrease diversion and expand continuing education initiatives to ensure that prescribers are aware of the potential for abuse and misuse of prescription opioids.11 A study by Pitt et al shows how a combination of different approaches is necessary to make a substantial impact on deaths from opioids.12 This study analyzed the effects of 11 policy interventions (acute pain prescribing, prescribing for transitioning pain, chronic pain prescribing, drug rescheduling, prescription drug monitoring programs [PDMPs], drug reformulation, excess opioid disposal, naloxone availability, needle exchange, MAT, and psychosocial treatment). Increases in life years and quality-adjusted life years and decreases in deaths were projected with increasing naloxone availability, expanding MAT, and increasing psychosocial treatment. The results of this study illustrate the benefits of a cross-collaborative, multimodal model to stem deaths from OUDs.

Attitudes toward chronic pain

Primary care providers commonly treat patients with chronic, non-cancer pain and account for nearly 50% of opiates dispensed.13 Opioid prescribing continues to be a contentious issue for many PCPs who may have negative attitudes regarding patients with chronic pain.14 The following factors contribute to the development of negative attitudes:

- Difficult patient interactions15

- Concerns about opioid prescribing, including addiction

- Diversion and regulatory scrutiny16

- Coexistent psychiatric morbidities among these patients16

- Concerns about the time-consuming nature of care for these patients16

- Compliance issues17

These concerns may result in physician reluctance to prescribe opioids, leading to suboptimal access to pain treatment.10,14 The results of a survey by Mendiola et al reflected negative attitudes toward chronic pain, with physicians reporting a lower regard for patients with substance use disorders than other medical conditions with behavioral components. More than half (54%) of respondents stated that they prefer not to work with patients with substance use who have pain.18 Negative attitudes toward chronic pain must be overcome in order to combat the opioid epidemic.

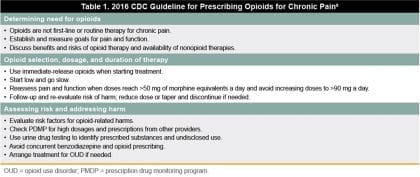

The 2016 CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain provides recommendations for PCPs who are prescribing opioids for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care.9 Based on a systematic review of best available evidence, 12 recommendations are given in three key areas—determining opioid needs; opioid selection, dosage, and duration of therapy; and assessing risk and addressing harm (Table 1).

An overarching criticism of the CDC guideline is the lack of emphasis that optimal pain management begins with identifying the cause of pain and the biopsychosocial mechanisms that contribute to its severity and associated disability.20 As a result, the CDC guideline may not adequately address the entire spectrum of pain management needs. The CDC guideline is voluntary rather than prescriptive, and clinicians should consider the circumstances and unique needs of each patient when providing care.9 The CDC guideline also recommends the use of non-opioid treatments in managing chronic pain when possible;9 however, multimodal pain management, including non-pharmacological modalities, may be unavailable or unaffordable. In a 2017 report, the President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis noted that the CDC guideline has resulted in practical challenges resulting from administrative and documentation burdens, difficulty accessing alternative forms of pain control, a lack of information on how to taper current levels of prescribing, and concerns that the pain management needs for all populations are not being adequately addressed.11

Although the CDC guideline does not endorse a maximum limit on opioid medicines or involuntary tapering, the lack of explicit guidelines has led to misinterpretation by legislators, pharmacy chains, insurers, and others who have used the guidelines to justify restrictions on opioid treatment. An editorial published in Pain Practice noted that the CDC guideline set up unrealistic expectations that can make prescribers reluctant to prescribe opioids the patient might urgently need.21 Furthermore, unintended harms may result from overly aggressive adoption of the CDC guideline, including withdrawal reactions, uncontrolled pain, anxiety for patients, and loss of trust in their physicians.22 In severe cases, some patients may turn to street drugs, increasing their risk of overdose, or resort to suicide.23

Pain overview

Pain is a complex biologic and psychologic phenomenon that is often poorly understood and inadequately managed by primary care providers because of insufficient education and training.24 A mechanism-based approach can be applied to the clinical assessment and management of pain.25 Pain mechanisms include predominantly neuropathic, predominantly nociceptive, and a new classification of predominantly nociplastic.26 Neuropathic pain is caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system. Nociceptive pain arises from actual or threatened damage to non-neural tissue and is due to the activation of nociceptors. Nociplastic pain arises from altered nociceptors despite no clear evidence of active tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors, or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain. It is important to recognize that patients may benefit from tailored and targeted treatments prescribed based on specific types of pain. For example, neuropathic pain often responds to antidepressants or anticonvulsants. Additionally, pain can be characterized by duration (eg, acute, chronic), which also affects treatment selection.

Acute pain involves primarily nociceptive processing areas in the central nervous system (CNS) and is not associated with changes in the CNS.27 Acute pain typically occurs as a normal response to surgery, acute illness, trauma, or other injury and is self-limiting, generally lasting from hours to days or a month after the precipitating event. The duration of acute pain is consistent with the time required for normal healing to occur.28 Acute nociceptive pain responds well to analgesics such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Chronic pain is defined as pain that lasts 3 months or more and is typically associated with changes in the CNS known as central sensitization.27 Chronic pain is often associated with alterations in brain centers involved with emotions, reward and executive function as well as central sensitization of nociceptive pathways across several CNS areas. For those with central pain syndromes (eg, fibromyalgia), centrally acting neuroactive compounds, such as certain antidepressant medications and anticonvulsants, may provide better relief than opioids.29 Development of central sensitization may occur over time with long-term opioid use and produce pain response to non-painful stimulus, which could lead to spontaneous pain (hyperalgesia and allodynia).

High-impact chronic pain has been identified as a subset within the chronic pain population who also have at least one major activity restriction, such as being unable to work outside the home, go to school, or do household chores. A study of high-impact chronic pain by Pitcher et al revealed that pain-related disability affects a substantial portion of the chronic pain population experiencing progressive deterioration in mental and physical health outcomes along with substantially higher healthcare usage.30 Multimodal treatment approaches are particularly important to reduce the impact of disability in patients with high-impact chronic pain.

The opioid landscape

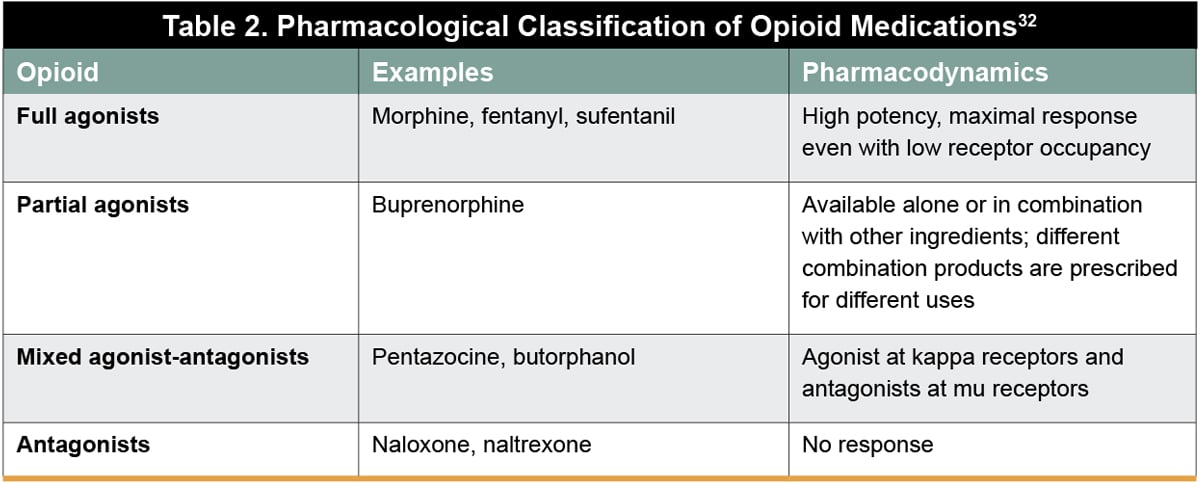

In a position statement on opioids, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) identified opioids as indispensable for the treatment of severe short-lived pain during acute painful events and at the end of life, with no other oral medication currently offering immediate and effective relief of severe pain.31 Opioid analgesics belong to a broad class of medications that include full agonists, partial agonists, mixed agonist-antagonists, and antagonists (Table 2).32 Opioids bind to opioid receptors (mu, delta, kappa, and opioid-receptor like-1 [ORL-1]) distributed widely throughout the central and peripheral nervous system and in the gastrointestinal tract, immune cells, pituitary gland, and skin.33

In a position statement on opioids, the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) identified opioids as indispensable for the treatment of severe short-lived pain during acute painful events and at the end of life, with no other oral medication currently offering immediate and effective relief of severe pain.31 Opioid analgesics belong to a broad class of medications that include full agonists, partial agonists, mixed agonist-antagonists, and antagonists (Table 2).32 Opioids bind to opioid receptors (mu, delta, kappa, and opioid-receptor like-1 [ORL-1]) distributed widely throughout the central and peripheral nervous system and in the gastrointestinal tract, immune cells, pituitary gland, and skin.33

Non-pharmacological options for pain management

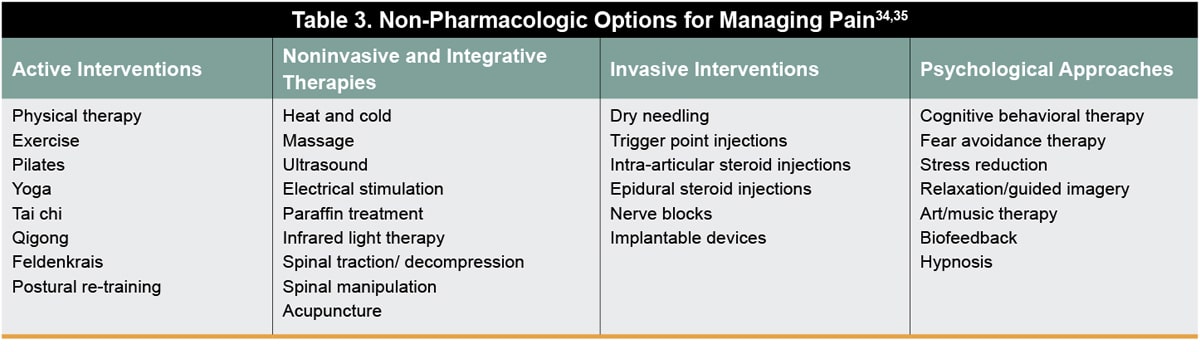

There are many nonpharmacological treatments that can be beneficial and should be explored and considered for the management of pain. These techniques may be used in conjunction with pharmacological treatments and include active interventions, noninvasive and integrative therapies, invasive interventions, and psychological approaches (Table 3).

There are many nonpharmacological treatments that can be beneficial and should be explored and considered for the management of pain. These techniques may be used in conjunction with pharmacological treatments and include active interventions, noninvasive and integrative therapies, invasive interventions, and psychological approaches (Table 3).

Evaluation of risk

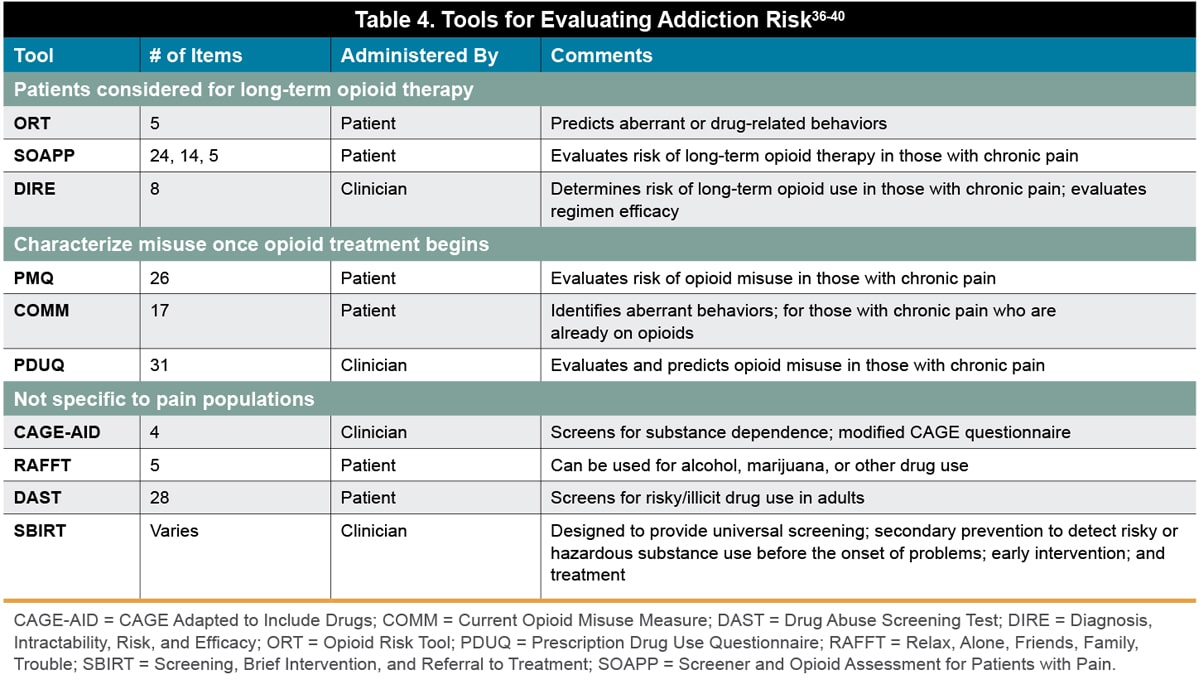

One approach to improve safe opioid prescribing practices has focused on screening, identifying, and monitoring patients who may be at risk of opioid-related harms prior to the prescription of opioids. An assortment of screening and risk assessment tools are available to identify patients at risk of opioid-related harm.36 These tools are generally used for the following purposes: 1) to assess risks for patients who  are being considered for long-term opioid therapy; 2) to screen for misuse once opioid treatments have begun; and 3) to screen for substance use not limited to opioid misuse (Table 4).

are being considered for long-term opioid therapy; 2) to screen for misuse once opioid treatments have begun; and 3) to screen for substance use not limited to opioid misuse (Table 4).

The management of pain is complex and difficult and is impacted by a variety of factors that reflect individual variability in the response to pain and its treatment. A holistic approach to pain management addresses the whole patient and incorporates physical, psychological, biological, spiritual, social, and cultural components that influence the patient’s experience.37 These integral components play a significant role in areas of everyday life and influence the experience of pain. Consideration of the components that influence the patient’s pain experience will help to formulate a treatment plan that best meets individual needs.

Look for Part 2 of this opioid education series on June 4, 2019 entitled Addressing the Opioid Epidemic: New Approaches to Safe and Effective Pain Management that will focus on implementing new practices for pain management and feature non-opioid approaches being adopted by oral surgery programs and the new Orthopaedic Trauma Association Clinical Guidelines for Pain Management in Acute Musculoskeletal Injury.

References

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Opioid overdoses treated in emergency departments. Identify opportunities for action. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/opioidoverdoses/index.html. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- International Narcotics Control Board. Narcotic Drugs – Technical Report. Estimated World Requirements for 2018. Available at: https://www.incb.org/incb/en/narcotic-drugs/Technical_Reports/narcotic_drugs_reports.html. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Understanding the epidemic. December 16, 2016. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), Office of the Surgeon General, Facing addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s spotlight on opioids. Washington, DC: HHS, September 2018. Available at: https://addiction.surgeongeneral.gov/sites/default/files/OC_SpotlightOnOpioids.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Jeffery MM, Hooten WM, Henk HJ, et al. Trends in opioid use in commercially insured and Medicare Advantage populations in 2007-16: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;362:k2833.

- McKinsey & Company. Why we need bolder action to combat the opioid epidemic. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/healthcare-systems-and-services/our-insights/why-we-need-bolder-action-to-combat-the-opioid-epidemic. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Dineen KK, DuBois JM. Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Can physicians prescribe opioids to treat pain adequately while avoiding legal sanction? Am J Law Med. 2016;42(1):7-52.

- Hoffman DE. Treating pain V. Reducing drug diversion and abuse: recalibrating the balance in our drug control laws and policies. Saint Louis University Journal of Health Law & Policy. 2016;1:231–310.

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49.

- Jamison RN, Sheehan KA, Scanlan E, Matthews M, Ross EL. Beliefs and attitudes about opioid prescribing and chronic pain management: survey of primary care providers. J Opioid Manag. 2014;10(6):375-382.

- The President’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis. 2017. Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/images/Final_Report_Draft_11-15-2017.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Pitt AL, Humphreys K, Brandeau ML. Modeling health benefits and harms of public policy responses to the us opioid epidemic. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(10):1394-1400.

- Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). Pain management and opioid abuse: a public health concern. July 2012. Available at: https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/patient_care/pain_management/opioid-abuse-position-paper.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Matthias MS, Parpart AL, Nyland KA, et al. The patient-provider relationship in chronic pain care: physicians’ perspectives. Pain Med. 2010;11(11):1688-1697.

- Chen JT, Fagan MJ, Diaz JA, Reinert SE. Is treating chronic pain torture? Internal medicine residents’ experiences with patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Teach Learn Med. 2007;19(2):101-105.

- Evans L, Whitham JA, Trotter DR, Filtz KR. An evaluation of family medicine residents’ attitudes before and after a PCMH innovation for patients with chronic pain. Fam Med. 2011;43(10):702-711.

- Mendiola CK, Galetto G, Fingerhood M. An Exploration of emergency physicians’ attitudes toward patients with substance use disorder. J Addict Med. 2018;12(2):132-135.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Pain Management and Regulatory Strategies to Address Prescription Opioid Abuse; Phillips JK, Ford MA, Bonnie RJ, eds. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2017 Jul 13. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK458660/doi:10.17226/2478. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Pain management best practices inter-agency task force – draft report on pain management best practices: updates, gaps, inconsistencies, and recommendations. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ash/advisory-committees/pain/reports/2018-12-draft-report-on-updates-gaps-inconsistencies-recommendations/index.html. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Pergolizzi JV, Jr., Raffa RB, Zampogna G, et al. Comments and suggestions from pain specialists regarding the CDC’s proposed opioid guidelines. Pain Pract. 2016;16(7):794-808.

- Busse JW, Juurlink D, Guyatt GH. Addressing the limitations of the CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic noncancer pain. CMAJ. 2016;188(17-18):1210-1211.

- Nicholson KM, Hoffman DE, Kollas CD. Overzealous use of the CDC’s opioid prescribing guideline is harming pain patients. Available at: https://www.statnews.com/2018/12/06/overzealous-use-cdc-opioid-prescribing-guideline/. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Stanos S, Brodsky M, Argoff C, et al. Rethinking chronic pain in a primary care setting. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(5):502-515.

- Chimenti RL, Frey-Law LA, Sluka KA. A mechanism-based approach to physical therapist management of pain. Phys Ther. 2018;98(5):302-314.

- Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, et al. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain. 2016 Jul;157(7):1382-1386.

- US Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense. Provider Pocket Guide Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain. Available at: https://www.qmo.amedd.army.mil/OT/OpioidTherapyProviderGuide_508_Web_FINALv1.1_NOV2017_PDF.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Hooten M, Thorson D, Bianco J, et al. Pain: assessment, non-opioid treatment approaches and opioid management. August 2017. Available from: https://www.icsi.org/guidelines__more/catalog_guidelines_and_more/catalog_guidelines/catalog_neurological_guidelines/pain/. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Reuben DB, Alvanzo AA, Ashikaga T, et al. National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop: the role of opioids in the treatment of chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):295-300.

- Pitcher MH, Von Korff M, Bushnell MC, Porter L. Prevalence and profile of high-impact chronic pain in the United States. J Pain. 2019;20(2):146-160.

- IASP statement on opioids, February 2018. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Advocacy/OpioidPositionStatement. Accessed January 26, 2018.

- VA South Central Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center. Pocket guide for clinicians for management of chronic pain. January 2017. Available at: https://www.mirecc.va.gov/VISN16/docs/pain-management-pocket-guide.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Chu R, Ciani A, Raouf M. Opioid Agonists, Partial Agonists, Antagonists: Oh My! Available at: https://www.pharmacytimes.com/contributor/jeffrey-fudin/2018/01/opioid-agonists-partial-agonists-antagonists-oh-my. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- American Chronic Pain Association (ACPA). 2018. ACPA resource guide to chronic pain management: an integrated guide to medical, interventional, behavioral, pharmacologic and rehabilitation therapies. 2018. Available at: https://www.theacpa.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ACPA_Resource_Guide_2018-Final-v2.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Chang KL, Fillingim R, Hurley RW, Schmidt S. Chronic Pain Management. FP Essentials™, Edition No. 432. Leawood, KS: American Academy of Family Physicians; May 2015.

- Duke Margolis Center for Health Policy. Strategies for promoting the safe use and appropriate prescribing of prescription opioids. February 15, 2018. Available at :https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/landscape_analysis_-_opioid_safe_prescribing_strategies.pdf. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- PDQ® Supportive and Palliative Care Editorial Board. PDQ Cancer Pain. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available at: https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/treatment/side-effects/pain/pain-hp-pdq. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Florida Medical Association (FMA). Prescribing Controlled Substances: Florida Laws and Clinical Guidelines. Tallahassee, FL.

- National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse (CASA) at Columbia University. Addiction Medicine: closing the gap between science and practice. Available at: https://www.centeronaddiction.org/addiction-research/reports/addiction-medicine-closing-gap-between-science-and-practice. Accessed January 26, 2019.

- Hudspeth RS. Safe opioid prescribing for adults by nurse practitioners: part 1. patient history and assessment standards and techniques. Journal for Nurse Practitioners. 2016;12(3):141–148.