To review CME/CE credit and disclosure information click here

Authors

Monica E. Peek, MD, MPH, MS; Joia A. Crear-Perry, MD; Marc Cohen, MD; Carmen Renee Green, MD; Hazel J. Harper, DDS, MPH; Otis W. Kirksey, PharmD; Jason Knutson, DO; Jenna C. Lester, MD; Monica Vela, MD; Augustus A. White III, MD, PhD; Noreen A. Iftikhar, MD; Kathleen A. Blake, PhD; Sharon A. Tordoff, BS.

Introduction

Racial and ethnic disparities in health care access and quality continue to exacerbate poor health, reduce quality of life (QoL), and increase morbidity and mortality among racialized minorities in the United States. The 2003 report, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care,”1 documented decades of glaring inequities in health care access, treatment, and outcomes, but as health disparities persist, it is clear they have not been adequately addressed. The COVID-19 pandemic amplified and illuminated the impact of disparities along socioeconomic status (SES) and racial lines. Monica E. Peek, MD, MPH, MS, Associate Professor of Medicine at the University of Chicago and health disparities researcher, noted that structural racism disproportionately put persons of color at increased risk of infection because of where they work (eg, essential jobs), live (eg, residentially segregated neighborhoods with high population density and poor housing ventilation), and play (eg, communities with fewer resources). Structural racism then led to inequities in access to COVID-19 protection (PPE), testing, and treatment. “Overall,” Dr. Peek said, “COVID outcomes are tied to pre-pandemic realities.”

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) define health disparities as “differences in the incidence, prevalence, mortality, and burden of diseases and other adverse health conditions that exist among specific population groups in the United States.”2 These groups include Black/African American, Hispanic/Latin American, Hawaiian Native/Pacific Islander, Native American/ Alaskan Native, and Asian Americans, as well as low-income, disabled, and elderly individuals. Structural racial inequalities are among the deeply rooted sources of health disparities and social determinants of health (SDoH) – the conditions in which people live, learn, work, worship, and age.3 These environmental determinants often define individuals’ interactions with the healthcare system and directly correlate with health disparities, including increased risk factor burden, preventable hospitalizations, morbidity, and mortality.

Understanding how racism affects health care and health requires a common language and understanding about terminology. Dr. Camara Jones4 describes three levels of racism: institutionalized racism, personally-mediated racism, and internalized racism. Institutionalized, or structural, racism is defined as differential access to goods, services, and opportunities based on race. Personally-mediated racism, or interpersonal racism, is defined as prejudice (differential assumptions about the abilities, motives, and intentions of others according to their race) and discrimination (differential actions toward others according to their race). Last, internalized racism is defined as the acceptance by members of stigmatized races of negative messages about their abilities and intrinsic worth.

Personally-mediated racism manifests in health care professionals’ (HCP) explicit and implicit biases, stereotyping, and discrimination, and is a key contributor and stand-alone factor in health disparities. Studies show that even when socioeconomic factors and health care access are equal to White Americans, minority populations are more likely to receive inferior health care.

The harrowing postpartum experience of world-renowned tennis star Serena Williams shed light on the harmful effects of racial biases in the ongoing maternal mortality crisis. “I almost died after giving birth to my daughter,” Williams, an African American, recounted after the birth of her daughter in 2017. A few hours after giving birth, Williams began experiencing shortness of breath. Due to her previous history of pulmonary embolism, she recognized this symptom to be a warning sign. Williams alerted hospital personnel but was repeatedly ignored or dismissed as being “confused”. Once addressed, complications from the embolism led to two surgeries and six weeks of bedrest.5 Williams, whose fame, wealth, and education increased her health literacy and health care access, still faced disparate care due to HCP biases.

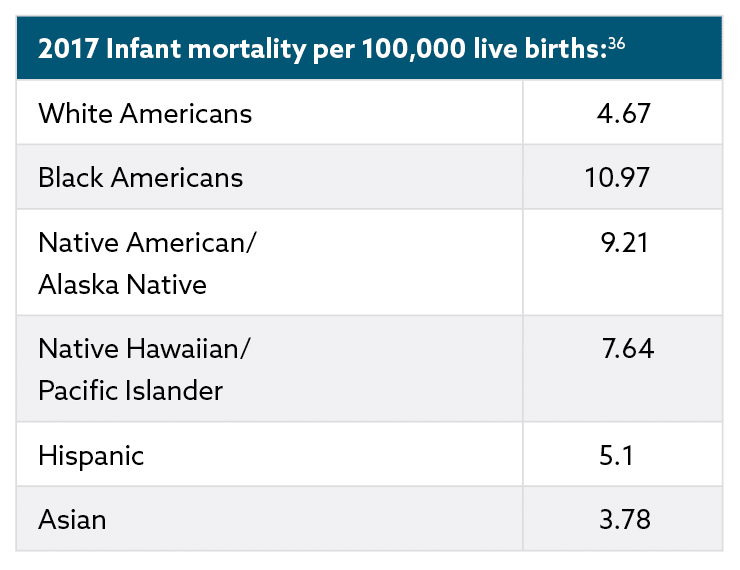

Health disparities data reveal that minority populations are impacted by inequities at every level of care. For example, Black patients are 30% more likely than White patients to die of heart disease,6 Native Hawaiian and Pacific Island populations have higher incidence of cardiovascular disease, and, on average, Native American populations succumb to heart disease at a younger age.7 In Black Americans, the age-adjusted death rate is 30% higher,8 and infant mortality rates are 2.4 times higher than White Americans.8,9 Health disparities are entrenched in historical and present-day institutionalized and personally-mediated racism, much of which drives SDoH. Hence, efforts to address health disparities through the lens of SDoH and risk scores alone have repeatedly fallen short.

The Forum

A recent and pivotal forum, “Addressing Unconscious Bias and Disparities in Health Care,” examined the fundamental causes of bias and how they manifest in modern clinical practice. Forum members also developed a call-to-action to highlight the multiple sources of disparate care and remove barriers to equitable care in meaningful and sustainable ways. Health care practitioners from varied disciplines, including primary care, maternal health, cardiology, dermatology, pharmacy, and oral health, voiced the need to design a system that served all patients’ health care needs. Moderated by Monica E. Peek, the panel acknowledged that while patient-practitioner interactions are critical to address immediate health disparities, structural solutions are needed to repair systemic problems.

Panel members outlined steps for HCPs to address health care inequities in minority populations. The first step is medical education. Information taught in classroom, clinical, and informal settings contributes to institutionalized and personally-mediated biases, and perpetuate misinformation about the historical frameworks responsible for modern health care disparities. Only by (re-)learning a more comprehensive and fact-based history of health care can clinicians better understand current racism in health care, health disparities, and sociopolitical medical mistrust among racialized minorities. Medical education must be combined with tangible steps that HCPs and civil leadership can put into action. Ultimately, large-scale, concrete, structural changes are needed to create a more equitable health system – a health care system that works for all patients regardless of race, socioeconomic status, or other social identities.

Background

Race and racism

The history of racism and racist policies in the United States infiltrates every sociopolitical arena, including health care. As forum members noted, this unpleasant history must be faced for sustainable change: “To transform health care, we must acknowledge the trauma of systemic racism and work together to solve it.” The very concept of race was developed socio-politically to infer unfounded biological differences; how race is assessed varies from culture to culture and has changed over time. Humans are more diverse within groups of people than between them, and traits, such as skin color, associated with the Western idea of race, are discordant, unrelated, and superficial.10 While race is not biological, racism has biological consequences.

Repeated long-term and generational racial trauma creates physiological changes, weathering physical, emotional, and mental health over time.11 These changes amplify during a person’s lifetime and may cause epigenetic changes that are passed on inter-generationally. Epigenetics, changes due to environmental influences from the womb and throughout one’s life, can alter gene expression, causing long-term damage.12 Changes that occur in the womb can persist, leading to poor health in adults.7,12-15 For example, on arrival to the United States, African immigrant women’s health status equaled American White women; however, within one generation, their children and grandchildren had lost that advantage.16 Disparities in exposure to environmental and psychosocial stressors, as well as physical toxins, can cause differential methylation of DNA, which has been associated with an increased risk of diseases such as breast cancer, small-cell lung cancer, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and depression.

As products of our society and environment, we each have biases related to race or ethnicity. Explicit or conscious bias are those behaviors associated with racism and deliberate discrimination. Implicit bias is unconscious; we may make snap judgements or adapt behaviors without being aware. These include the biased cognitive shortcuts we rely on in high stress situations, when there is incomplete data and HCPs have to make clinical decisions.17 Once we understand what biases look like in health care, we can address them at the individual and institutional level.18

Basing clinical decisions on assumptions about patients, rather than their presenting symptoms and reported history, leads to erroneous decision-making that disproportionately harms racial and ethnic minority patients.17 Unconscious bias can manifest as assumptions about who “deserves” care, whether a patient complaining of pain is merely a “drug seeker”, and whether a “non-compliant” patient has barriers to treatment adherence or is merely unmotivated. Dismissing symptoms that do not fit a “classic” presentation for only one group is also a form of bias. Symptoms may be “classic” for only one group of people. Patients from minority populations recognize negative biases, which reduces patient follow-through and creates patient-practitioner distrust.

Medical racism

The medical profession’s mistreatment of racial and ethnic minority groups predates the founding of the United States and stems from colonialism and the slave trade. The devaluation, subjugation, and exploitation of minority groups over 400 years became engrained in the structures and organizations of society, including medicine.

People of color, primarily within the slave trade, were viewed as commodities and exposed to horrifying human medical experimentation.19,20 Most famously, gynecologist James Marion Sims subjected enslaved women to vaginal and other gynecological procedures without anesthesia.19 Myths that Black people have thicker skin, fewer nerve endings, or feel pain less acutely than White people originated from these experiments. Enslaved persons desiring freedom were classified as “mentally ill” and subjected to torture “treatments”.21-23 Individual racist practices became codified through policies and programs, such as forced sterilization based on the pseudoscience of eugenics,24-28 public health programs such as the Tuskegee Syphilis study,14,29 the closing of over 500 Black hospitals,30 and the testing of skin care treatments on Black inmates from 1950 to 1970, among others.31

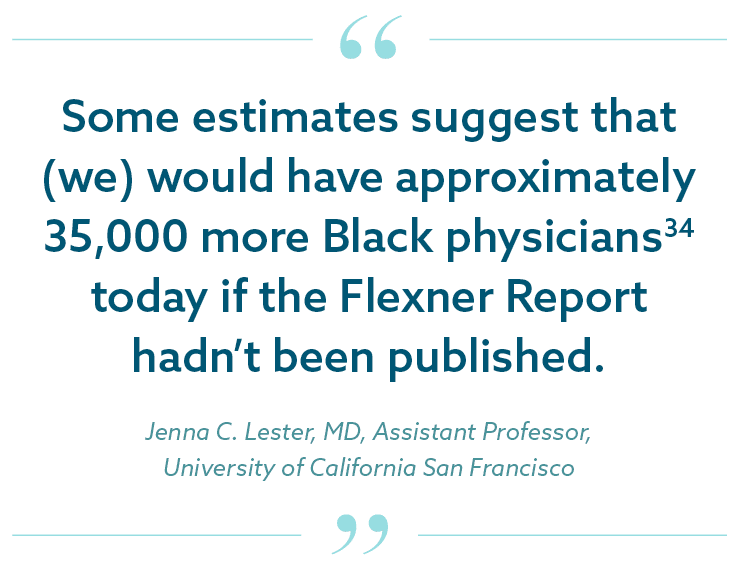

This historical mistreatment and marginalization became embedded in the medical community. For example, the American Medical Association (AMA) originally created policies excluding Black doctors from membership. This restricted many Black physicians from practicing medicine, having hospital privileges, and connecting with other health professionals.32 The AMA also commissioned the Flexner Report, which recommended closing over 500 predominantly Black hospitals, and all but two Black medical schools, thus severely limiting the access of Black patients to physicians and hospitals for medical care.32,33

Social determinants of health

The U.S. government has officially recognized health care inequities for decades. In 1999,35 Congress commissioned the Institute of Medicine to create a report on health care disparities; however, this awareness has not significantly improved health care disparities. The report, “Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Care,” noted that racial and ethnic differences persist beyond access-related factors or preferences, and cited institutional health care factors (ie, structural racism) and discrimination (ie, personally-mediated racism) as the two primary causes.1,35 The World Health Organization recognized that SDoH impact health access and outcomes.3 In the United States, many of these stem from everyday structural racism and bias. For example, highways built through low-income, racial and minority neighborhoods created physical barriers between residents and the resources they needed outside of their communities. These barriers are not accidental, but the result of intentional policies for socio-politically devalued communities.

Systemic racism leads to poor health outcomes in multiple ways because many SDoH variables are intersectional. Community factors, redlining, food deserts, and a lack of pharmacies and public transportation compound disparities for minority populations and increase the risk of chronic conditions, such as obesity, hypertension, diabetes, and asthma.

These data on health disparities are the tip of the iceberg:

- Death rates for Black Americans compared to White Americans are higher: Cardiovascular disease 34%, infections 21.1%, trauma 10.7%, diabetes 8.5%, renal disease 4.0%, and cancer 3.4% higher9

- Of male individuals in same-sex relationships who received care for HIV, 24% were Black and 43% were White; however, Black individuals were more likely to be diagnosed with HIV37

Diabetes also impacts minority populations disparately. Over 20% of Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island adults, over 18% of African American adults, and nearly 12% of Hispanic/Latinx adults are impacted by diabetes.42 Native American populations have 3.5 times higher rates of kidney failure and African American populations are 50% more likely to experience diabetic retinopathy. Complications from diabetes include blindness, amputation, kidney disease, cardiovascular disease, and stroke.42 Studies show that obesity and diabetes are associated with low-income neighborhoods with less access to grocers and higher police-recorded crime.43-45 Those who are food insecure were more likely to be admitted to hospital for hypoglycemia than adult patients with higher incomes.

Disparities Across the Health Care Spectrum

Members of the CME Outfitters (CMEO) forum came from a variety of specialties, each bringing a unique point-of-view of how health disparities impact minority populations. The discussions affirmed that while specifics may vary, the underlying themes intertwine and overlap. Outlined below are some of the health arenas and clinical manifestations of health disparities by medical specialty discussed in this expert CMEO forum.

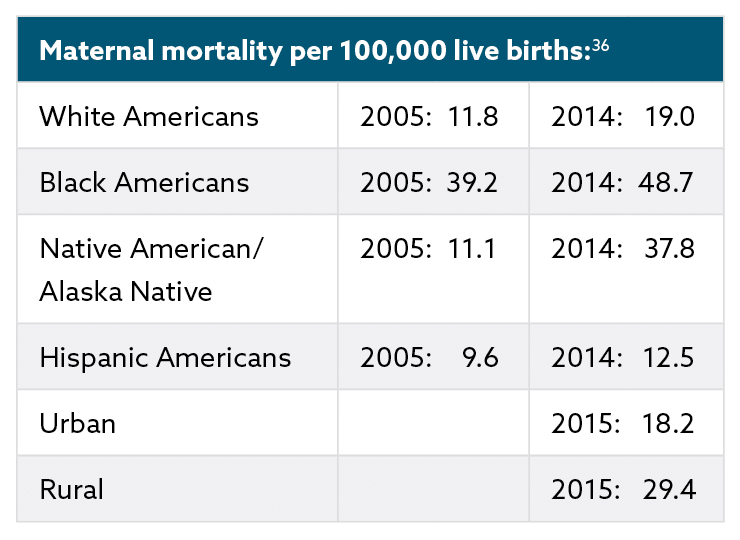

Disparities in maternal health

Joia A. Crear-Perry, MD, FACOG, of the National Birth Equity Collaborative, discussed the U.S. maternal health crisis and the need to create birth equity for minority pregnant people. As a physician and advocate for legislative change for maternal health, Dr. Crear-Perry connected maternal inequities to the devaluation of people of color in the United States. While other developed nations invest in their citizens by providing paid family leave, free childcare, and standardized national health care, the United States lags behind in maternal and infant care. Pregnant people of color, in particular, lack equitable maternal care with devastating outcomes in morbidity and mortality rates. Individuals in the United States that die due to poor maternal health are three times more likely to be Black and twice as likely to be Native American than White.46 Medical practitioners and policy makers alike must create a sustained commitment to maternal care that provides accountability, equity, empathy, safety, and trust, and is free from racism.

Reproductive health and pregnancy are adversely affected not only by health care professionals’ biases, but also by SDoH and structural inequities. Housing, food, or income insecurity, environmental stresses, inadequate health care services or insurance, and low education converge to cause serious clinical issues, such as eclampsia, obstetric complications, cardiac disease, and acute renal failure. The maternal mortality crisis is evident in the data, which includes:

- In 2017, the United States ranked 61st in the world for maternal mortality47

- In the United States, 65% of maternal deaths are preventable46

- Pregnancy related mortality is 2.4 times higher46 than it was in 1987

Disparities in pain treatment

Carmen Renee Green, MD, a Professor of Anesthesiology, Obstetrics & Gynecology, and Health Management & Policy at the University of Michigan’s Schools of Medicine and Public Health, discussed the unequal burden of pain on people of color.48 The pervasive judgement about who deserves pain care and who does not permeates American culture. Health professionals frequently undertreat people from racial and ethnic minority populations for pain, believing their complaints of pain to be inauthentic,49 which further exacerbates distrust between racial and ethnic minority patients and HCPs. While treated less, people of color have higher pain risk due to structural racism. That is, environmental circumstances, including community violence, and the disproportionate burden of chronic diseases, such as painful diabetic neuropathy and more, put racial and ethnic minority populations at increased risk for conditions requiring pain management. Untreated and undertreated pain decreases SES (due to job loss, for example), overall QoL, and life expectancy, and increases comorbid risks, including severe depression and suicide ideation.48,50

Pain care disparities stem, in part, from how the medical and criminal justice system has dealt with the opioid epidemic. White populations, who are as likely to have substance use problems as other racial or ethnic populations, have typically been viewed sympathetically as “victims” of addiction with a “biomedical” problem. In comparison, substance use issues that predominantly afflict people of color have been criminalized. These inequities in the legal system and media magnify racial biases; HCPs are more likely to label pain patients from Black/African American and Hispanic/Latinx populations as “drug seekers”.50 Ironically, patients who are inadequately treated for pain may be forced to turn to excess over-the-counter pain medications or seek relief from addictive substances.

Studies show that HCPs’ biases lead to disparate pain care even when the guidelines for analgesic use are clear, such as during postoperative care or during childbirth.48 Disparities in medical treatments to alleviate musculoskeletal and other causes of chronic pain, including dental pain, compound the problem. For example, while White patients make up 62% of the population, they undergo hip and knee arthroplasty procedures at 80% and 77% respectively. Black patients, at 12% of the U.S. population, receive only 6% and 7% of surgeries; Hispanic patients who make up 16% of the population, receive even less, only 4% and 5% of surgeries.51 As a result, White patients are more likely to have their pain cured through surgical interventions, while racial and ethnic minorities disproportionately rely on pharmaceutical regimens for pain control. Furthermore, Black patients were less likely than White patients to use complementary and alternative pain treatments, such as acupuncture, biofeedback/relaxation services, and manipulation/chiropractic services.52,53

The data are clear on disparities in pain care:

- Approximately 11%-40% of Americans suffer from chronic pain54

- Black patients receive 57%-74% less analgesics for long-bone fractures than White patients55

- Black patients are 22% less likely than White patients to receive pain medication56

- Endometriosis, a painful gynecological condition,55 is underdiagnosed and undertreated in Black patients

- Hispanic patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain have 28% higher depression scores57

Disparities in surgical care

Augustus A. White III, MD, PhD, an Ellen and Melvin Gordon Distinguished Professor of Medical Education at Harvard Medical School and author of the memoir, Seeing Patients: A Surgeon’s Story of Race and Medical Bias, that details unconscious bias in health care, discussed the need for a humanitarian approach as a means to achieve equitable health care. He described the current health system as “survival of the fittest,” where access to health care and treatment was based on one’s social and financial capital as manifested by measures such as insurance, zip code, and social networks.

The key, Dr. White said, was empathy. Empathy for the patient helps both patient and physician. Clinicians with high levels of empathy experience lower levels of burnout and higher levels of work satisfaction. Patients who report poor communication with their physician also report higher levels of practitioner dissatisfaction. Dr. White emphasized the critical importance of physician–patient communications with racial and ethnic minority patients, as surgeons, in particular, are a specialty where communication skills are infrequently prioritized. Empathy can start by developing cultural humility and being aware of racial bias in health care. In one study, only one-third of surgeons acknowledged that racial and ethnic disparities exist in surgical care.58

Surgical specialties are also the least diverse in health care: 79.3% of surgeons identify as White and only 2.3% as Black.59-61 Racialized minorities receive disparate surgical care across surgical specialties, from orthopedics to surgical oncology, with resulting disparities in health outcomes. Like other areas of health care, structural inequities in access to surgical care affect surgical outcomes among people of color. One study showed that Black patients traveled 8.9 miles further than White patients to reach high volume hospitals (HVH), which have better surgical outcomes. Only 23% of Black patients versus 60% of White patients had access to an HVH.62

Disparities in cardiovascular disease

Marc Cohen, MD, Chair, Department of Medicine at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center, provided an overview of the significant disparities in cardiovascular disease (CVD) care and patient outcomes. Heart disease is the leading cause of death in the United States and globally, yet people of color disproportionately bear the disease burden. Black Americans are 30% more likely to die from CVD than White Americans, and individuals from Native American and Pacific Islander populations succumb to heart disease at disproportionally younger ages.63 Racial and ethnic minority patients have lower rates of referral for treatments, such as cardiac catheterization64 and interventional procedures,65 compared to White patients. Dr. Cohen stated that racial disparities in CVD treatment, such as higher rates of limb amputation (rather than revascularization) for peripheral vascular disease among racial and ethnic minorities, should be labelled as treatment failures, as the underlying cardiovascular disease is itself untreated and patients can be condemned to substantially different qualities of life (eg, ambulation with a wheelchair).

The data on disparities in CVD care and outcomes are alarming:

- From 1980-2014, deaths from CVD decreased, but disparities among racial and ethnic minorities did not, particularly in marginalized counties (eg, low levels of education, high rates of crime)66

- Black people are 30% more likely to die from CVD than their White counterparts6

- CVD accounts for 1/3 of the disparity in potential life-years lost between Black and White people9

- Black patients had 37% higher risk of amputation instead of limb-saving revascularization compared to White patients67

Disparities in dermatology

Addressing disparities in dermatology, Jenna C. Lester, MD, Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the University of California, San Francisco, discussed how people of color receive fewer dermatological screenings, are disproportionately excluded from clinical trials, and are underrepresented in medical textbooks, online dermatology resources, and other educational materials.68,69 “The dermatological conditions of people of color are not prioritized, said Dr. Lester. Racial and ethnic minority patients are less likely to receive dermatology treatments and prescriptions,70 and Black patients are often diagnosed with later stages of skin diseases.63,71-73

Because conditions, such as eczema, acne, and skin cancer, may present differently among persons of color, they are often underdiagnosed, misdiagnosed, and undertreated.70,73-77 While self-examinations are important tools in dermatology, these often miss melanoma among racialized minorities.75 For example, acral lentiginous melanoma is more common in Black individuals, but these lesions present in areas often unexposed to the sun (eg, soles of the feet, palms of the hands, hips) which are inspected less frequently during skin examinations. Disparities in dermatological care increase morbidity and mortality for people of color, subjecting them to unnecessary pain, scarring, infections, isolation, mental health issues, reduced QoL, and increased mortality. A sample of the data on dermatological disparities include:

- Melanoma 5-year survival rate: White patients 92% versus 70.4% of Black patients (includes Hispanic) and 86.0% of American Indian/Alaska Native patients (includes Hispanic)71

- Only 4.5% of medical textbooks show dermatological conditions on darker skin tones78

- Less than 2% of skin cancer awareness campaigns mention racial and ethnic minorities68

- Medical students only identified squamous cell carcinoma 14.9% of the time on skin of color (Fitzpatrick skin phototype IV-VI) versus 45.6% on light skin (Fitzpatrick skin phototype I-III)79

Disparities in oral health

Hazel J. Harper, DDS, MPH, outlined how oral health care is disconnected from the rest of health care, reducing both HCP and patient oral health literacy and impacting patient outcomes. She noted that only 12% of the U.S. population is proficient in oral health literacy.80 Dr. Harper founded the Deamonte Driver Dental Project after learning about Deamonte Driver, a 12-year-old who tragically died after an untreated dental abscess led to a fatal brain infection. Deamonte’s death, like many others, was avoidable, as insurance barriers kept him from accessing health care. His mother was unable to find a dentist that accepted Medicaid, a problem not uncommon among persons without private insurance. As a result, children from low-income and racial and ethnic minority families are less likely to receive preventive dental care and more likely to have cavities.81 In children, tooth decay is five times more common than asthma.82

Oral health challenges also impact adults. Twenty-nine percent of adults, and 62% of adults over 65 years of age, lack dental insurance.83 Furthermore, there is a shortage of dental health professionals, particularly dentists of color, in areas where dentists are needed most.84 Only 3.8% of dentists are Black and 5.9% Hispanic, while over 70% are White; however, only 39% of White dentists accept Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program, compared to 63% of Black dentists and 51% of Hispanic dentists.85

During the panel discussion, Dr. Harper emphasized that access to dental health professionals is only partly responsible for oral health care disparities in racial and ethnic minority communities. The deliberate separation of medical and dental insurance, and the lack of interprofessional collaboration between the medical and dental communities, also contribute to oral health disparities. Medical practitioners are often unaware of the impact of dental health on general health, including chronic conditions such as diabetes,83 CVD86,87 and peripheral artery disease,84 and rheumatoid arthritis.86 Additionally, people from minority populations may have higher risks of delayed surgical procedures or chemotherapy treatments due to poor dental health and associated risks of bacteremia, endocarditis, and sepsis. By collaborating, medical and dental practitioners can treat patients more comprehensively. For example, changes during pregnancy can impact oral health, which can, in turn, affect maternal and infant health outcomes.88 Dentists must ally with medical practitioners, to identify and prevent oral health and general health conditions at early stages, and understand that interprofessional clinical collaboration is a measure of professional competency.

Disparities in pharmaceutical care

To understand the pharmacist’s role in addressing health care disparities, Otis W. Kirksey, PharmD, RPh, CDCES, BC-ADM, shared his experiences with helping low-income patients overcome barriers to accessing prescription medications. Pharmacy deserts, like food deserts, create voids in neighborhoods, leaving patients unable to access necessary medications. In the United States, 150 counties do not have a pharmacy. Chain drugstores are more common in White/urban neighborhoods,89 with 30% more pharmacies in White communities overall.90 However, the absence of a pharmacy is only part the barrier that low-income patients face in accessing medications. Pharmacies that do not accept Medicaid are effectively unavailable to many patients, even if present in the community.

The high co-pay of some prescription drugs creates additional barriers to patients. Dr. Kirksey described how many clinicians are unaware of prescription costs or which medications are covered by Medicaid. These high out-of-pocket expenses are a substantial contributor to medication non-adherence. To address this, HCPs should have frank and open discussions about barriers to accessing prescription medications. In addition, pharmacists should routinely be proactive about identifying lower-cost alternatives, communicating with clinicians to modify prescriptions, and educating patients about their medications. Pharmacists can also educate patients on chronic conditions, such as diabetes, and play an integral role with the clinical team in chronic disease management (eg, adjusting medications according to algorithms).91-93

Disparities in patients with limited English proficiency

Patients with limited English proficiency (LEP) are at particular risk of health care disparities because communication problems are the root cause of 59% of serious adverse events.94 Between 44,000-98,000 people succumb to medical errors in hospitals each year,95 and roughly 25 million people in the United States have LEP. Monica Vela, MD, FACP, Professor of Medicine and Associate Vice Chair for Diversity at the Pritzker School of Medicine, explained that the absence of or inappropriate use of interpreters (eg, using family members) can cause patient harm and is a form of structural violence. Interpreters increase LEP patients’ full comprehension of their disease states and treatment plans, and can improve patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and health outcomes.

When patients lack clear medical information in a language they understand, inadequate care can result, leading to poor health outcomes and higher health care costs. Poor communication leads to improper medication use, serious medical errors, improper tests, and patient harm.96 Studies show that patients with LEP have, on average, longer inpatient or emergency room stays, receive fewer preventive services, and are charged 39% more.95,97,98

HCPs often believe professional interpreters are not necessary, using family members or staff to translate instead. Currently, only 40% of HCPs take advantage of interpreters. However, only trained, certified interpreters should be used as they are trained to ensure that patients and practitioners have clear communication. Family and staff may not convey information or translate medical information correctly or completely.

Providing interpreters for patients is respectful and also a legal obligation. A simple patient screening can assess language needs prior to appointment times so interpreters can be arranged. Practitioners should ask a two-part language question: 1) “How well can you discuss your symptoms in English? (not at all, not well, well, very well)” and 2) “What language would you prefer to speak with your physician?” These responses should be noted in the patient’s chart and interpreters and language appropriate educational materials and documents should be available.

Trained interpreters are often available but not implemented in a clinical setting. Practitioners may think arranging for an interpreter takes too much time;99,100 however, when interpreters are used, patients with LEP have shorter hospital stays and are less likely to be readmitted.97 One in five patients with LEP avoids seeking health treatment, has no primary care provider, and lacks preventive services due to language barriers, leading to further health disparities.

Changes to Address Heath Disparities

Forum members recognized that knowledge of disparities and their complex origins is essential to reducing current health care disparities. Actionable solutions at the individual, personally-mediated, and structural levels are necessary to repair the broken health systems providing inequitable care. While structural changes are critical for long-lasting change, every HCP is an immediate “gate-keeper” to the public’s health resources and, as such, has a vital role in increasing the equitable distribution of health care resources.

A focus of the panel was the need to educate health professionals, trainees, and students on the causes and impacts of inequitable health care. Education programs on health disparities for current HCPs is also necessary to reduce biases and illuminate the power structures that marginalize not only patients, but minority health professionals as well. By reimagining medical education and training, health care disparities can be diminished.

Some racial stereotypes and untruths are perpetuated in medical training, which can reinforce negative biases held by medical trainees. For example, medical education curricula throughout the country have incorrectly taught that Black people are more likely to use illicit substances.48 A study of 418 medical students found that many medical myths are prevalent:101

- Over 46% of first-year students believe “Black people’s blood coagulates more quickly than White people’s”

- Nearly 20% of medical students think “Black people have less sensitive nerve endings than White people”

- Between 37%-89% of medical students and residents believed “Black people have thicker skin than White people”

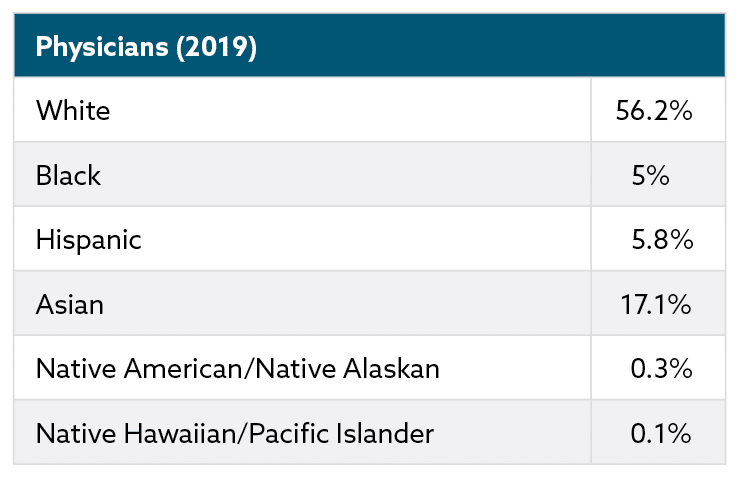

Biases in graduate medical education can affect the academic trajectory of racial and ethnic minority trainees, who are vastly underrepresented as health professional students. Only 6% of medical students are Black, 5% Hispanic,60 and less than 1% Native American.102 These numbers have not improved in the past several decades. Students can internalize the biases presented during medical education as well as personal experiences with racism. One study found that 24% of medical trainees reported racial discrimination.103 Racial and ethnic minority trainees leave residency programs at higher rates than White trainees and are less likely to enter specialties with low diversity, such as cardiology, dermatology, and orthopedic surgery.104,105

During training, medical residents provide primary care for patients who are more likely to be uninsured and from low-income and racial and ethnic minority communities. These resident clinics are often staffed differently than practices of attending physicians at the same institutions, where patients are more likely to have private insurance. Resident clinics often receive fewer resources, such as nursing staff, social workers, and other support services. This two-tiered system can make addressing the needs of medically complex patients more challenging, reinforce racial stereotypes about treatment adherence, send an implicit message that vulnerable patients are less deserving of high-quality medical care, and discourage medical trainees from working in underserved communities.106

A shift in medical education priorities and curriculum could create a learning environment less conducive to bias. The panel stressed the need for a more diverse, structurally-competent student body and faculty with strong interpersonal skills, high levels of empathy, and a desire to understand the lived experience of persons from marginalized communities. Achieving this would require many decisive actions, such as evaluating student applicants on emotional intelligence as well as biomedical knowledge, incorporating required coursework and training in structural inequities and bias in health care, addressing the financial needs of low-income applicants, and more. Augustus White remarked how creating a respectful and inclusive environment can reduce burnout, isolation, and depression.107,108

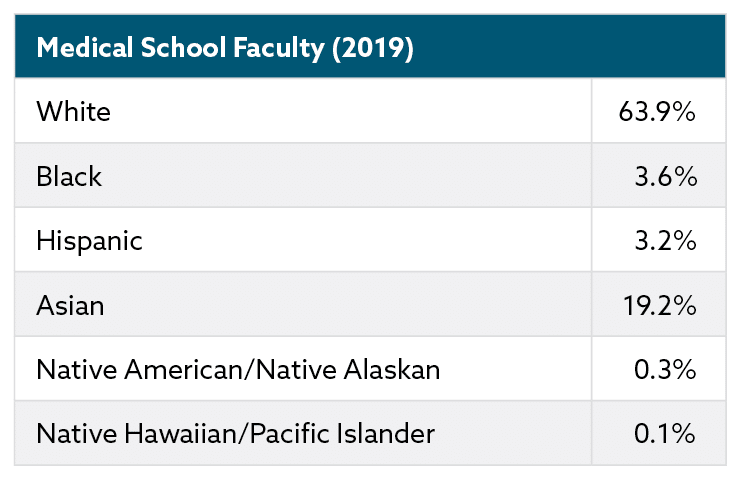

The numbers below portray the current level of diversity among physicians and physician educators:59

How can medical professionals lead change?

By learning more about bias and racism, medical professionals can commit to improve health care disparities in their immediate spheres of influence.18 The first step is to examine unconscious biases, to understand privilege and anti-racism, and then to change behaviors. HCPs may also benefit from acquiring cultural humility – being willing to learn about patients’ cultures but understanding that competency can never be attained. This humility develops acceptance of someone who may be perceived as “other” and allows practitioners to listen to patients with empathy – the first step to building trust. When patients and HCPs trust one another, health care disparities can be reduced. Patients that feel valued and heard will be more open to understanding their health conditions, treatments, and risks.

How can we change health care systems?

To change health care systems so they work for everyone, particularly our most marginalized populations, forum experts agreed that we should start by reimagining what health care can be at its best: a system where patients of color have optimal, high-quality care and can thrive; a system that can foster well-being and joy among populations that have been historically marginalized and mistreated; a system that puts patients first, respects and values their lived experience, and meets patients where they are—physically, socioculturally, and linguistically. This requires substantially diversifying the health care workforce and engaging patients and communities in redesigning physical spaces, policies, and procedures to affirm and value the lives and well-being of people of color. This means integrating the work of quality improvement with that of health equity within health care systems, so that innovations and improvements in health care delivery are done with health equity in mind. For example, as health care systems build upon the telehealth infrastructure put in place during the pandemic, they should do so with a specific goal of reaching underserved populations who have limited technological access and digital literacy. During the forum, Jason Knutson, DO, Medical Director for AveraNow, discussed how virtual care can help address disparities by reaching those with geographic and transportation barriers to care. He described how, in 2020, the AveraNow virtual care program worked with public health officials to screen a local immigrant population and then virtually monitor COVID-19 positive patients from home until some patients needed escalated care at medical centers.

Providing health care and health education via mobile units, and in collaboration with community-based organizations (eg, faith-based organizations, barber shops), has also shown promise to engage communities where they are.91-93,109 Expanding the health care team to routinely include pharmacists, dentists, community health workers, interpreters, behavioral health specialists, and others will go a long way in providing the comprehensive, holistic care that patients need. Collaborative team-based care is considered the standard in health care delivery, but its implementation in a patient-centered fashion remains an elusive goal. Having empowered patient and community advisory boards that can help shape how health care systems deliver care and interact with patients and families is an important, and underutilized, mechanism for creating patient-centered systems with the end user in mind.

How can we address social determinants of health?

There has been a lot of recent health policy interest in addressing social determinants of health within health care as a way to reduce health care costs and improve health outcomes for the most vulnerable patient populations. The National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine 2019 report110 on medical and social care integration created a framework for understanding how health care sector investments around social determinants of health can be most effective. The framework includes: Awareness (understanding patients’ socioeconomic circumstances and their specific social needs), Adjustment (tailoring health care delivery to meet patients’ social risks), Assistance (directing interventions to address the social barrier), Alignment (working with and investing in existing community-based resources), and Advocacy (promoting policies that address health and social needs).

As health care systems address social determinants of health (eg, food insecurity, transportation barriers, unstable housing), it is important to remember that structural inequities require aligned structural solutions that account for systemic effects of racism and sexism. For example, transportation is a major barrier for racial and ethnic communities in accessing health care and other health-promoting goods and services. In response, many interventions have utilized vouchers for public transportation or partnered with ride-share services as a solution. However, Dr. Crear-Perry reminded the panel that it was intentional policies in the 1960s that placed new highway systems in the middle of Black communities, thereby destroying their internal-built environments and physically isolating them from external resources. This type of structural racism directly resulted in the “transportation barriers” many face today. Reimagining transportation systems and policy, rather than merely using vouchers to sustain current systems, would be more effective at addressing the root cause of the problem.

Disparities in health and health care persist despite major advances in medicine and public health in the past decades. Racial, ethnic, and other minority populations in the United States are at disproportionate risk of lacking access to care, receiving inferior care, and experiencing worse health outcomes from preventable and treatable conditions. Health disparities stem from deep-rooted structural racism that the very foundation of this nation is built upon. These systemic inequities are compounded by institutionalized and personally-mediated racism within health care systems. Eliminating disparities in health care and health outcomes is a national priority and requires a multi-level and multi-pronged approach. HCPs play a pivotal role in shifting a system of disparate care to a truly patient-centered and equitable one that addresses the social determinants of health. By building patient trust, holding ourselves accountable, creating diverse work teams that are structurally competent, and mitigating implicit biases, we can begin to foster change that advances the health of all patients, particularly those most marginalized. These efforts, when aligned with public policies, such as a livable wage, paid sick leave, universal health care, and others, can make real progress in creating health equity among racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. We have much work to do.

References

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (U.S.); 2003.

- Health disparities. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. National Institutes of Health. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/healthdisp/index.htm. Published April 2017. Accessed June 3, 2021.

- Commission on social determinants of health. Who.org. 2006. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EIP-EQH-01-2006. Published October 20, 2006. Accessed May 28, 2021.

- Jones CP. Levels of racism: A theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Pub Health. 2000;90(8):1212-1215.

- Serena Williams: What my life-threatening experience taught me about giving birth. CNN.com. 2018. https://www.cnn.com/2018/02/20/opinions/protect-mother-pregnancy-williams-opinion/index.html. Published February 20, 2018. Accessed May 28, 2021.

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Arias E, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Report. 2021;69(13):1-83.

- Glynn P, Lloyd-Jones DM, Feinstein MJ, Carnethon M, Khan SS. Disparities in cardiovascular mortality related to heart failure in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(18):2354-2355.

- Gravlee CC. How race becomes biology: Embodiment of social inequity. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2009;139:47-57.

- Wong MD, Shapiro MF, Boscardin WJ, Ettner SL. Contribution of major diseases to disparities in mortality. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(20):1585-1592.

- What is race?: Is race for real? Race – The power of an illusion. PBS.org. http://www.pbs.org/race/000_General/000_00-Home.htm. Published 2003. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- Geronimus AT. Understanding and eliminating racial inequalities in women’s health in the United States: the role of the weathering conceptual framework. J Am Med Womens Assoc 1972. 2001;56(4):133-136.

- National Scientific Council on the Developing Child (2010). Early experiences can alter gene expression and affect long-term development: Working Paper No. 10. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/early-experiences-can-alter-gene-expression-and-affect-long-term-development/. Published May, 2010. Accessed May 7, 2021.

- Warne D, Lajimodiere D. American Indian health disparities: Psychosocial influences. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2015 Oct;9(10):567-579.

- Sacks TK, Savin K, Walton QL. How ancestral trauma informs patients’ health decision making. AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(2):E183-E188.

- Warne D, Frizzell LB. American Indian health policy: Historical trends and contemporary issues. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(S3):S263-S269.

- David RJ, Collins Jr JW. Differing birth weight among infants of U.S.-born Blacks, African-born Blacks, and U.S.-born Whites. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(17):1209-1214.

- Oxtoby K. How unconscious bias can discriminate against patients and affect their care. 2020;371:m4152.

- White AA, Stubblefield-Tave B. Some advice for physicians and other clinicians treating minorities, women, and other patients at risk of receiving health care disparities. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:472-479.

- Morgan JL. Partus sequitur ventrem Law, race, and reproduction in colonial slavery. Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism. 2018;22(1(55)):1-7.

- Owens DC, Fett SM. Black maternal and infant health: Historical legacies of slavery. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(10):1342-1345.

- Willoughby CDE. (2018). Running Away from Drapetomania: Samuel A. Cartwright, Medicine, and Race in the Antebellum South. J South Hist. 2018;84(3):579-614.

- Roberts DE. Killing the Black body: Race, reproduction, and the meaning of liberty. Vintage Books: U.S.

- Wall LL. The medical ethics of Dr. J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record. J Med Ethics. 2006;32(6):346-350.

- Stern AM. That time the United States sterilized 60,000 of its citizens. Huffpost.com https://www.huffpost.com/entry/sterilization-united-states_n_568f35f2e4b0c8beacf68713. Published January 7, 2016. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- Black E. War against the weak: Eugenics and America’s campaign to create a master race. In: Crawford KJ, Hamrick MS, Reynolds JT, eds. Perspectives in History. Dialog Press; 2012: pp. 77-80.

- Price GN, Darity Jr WA. The economics of race and eugenic sterilization in North Carolina: 1958–1968. Econ Hum Biol. 2010;8(2):261-272.

- Patel P. Forced sterilization of women as discrimination. Public Health Rev. 2017;38(1):1-2.

- Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(7):1128-1138.

- S. Public Health Service syphilis study at Tuskegee. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/. Published April 22, 2021. Accessed May 6, 2021.

- Wilson T. History of Black hospitals examined. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/history-of-black-hospitals-examined/2012/02/07/gIQAWqvx1Q_story.html. Published February 9, 2012. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- Adamson AS, Lipoff JB. Reconsidering named honorifics in medicine – the troubling legacy of dermatologist Albert Kligman. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(2):153-155.

- Baker RB, Washington HA, Olakanmi O, et al. African American physicians and organized medicine, 1846-1968. JAMA. 2008;300(3):306-313.

- Savitt T. Abraham Flexner and the Black medical schools. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1415-1424.

- Campbell KM, Corral I, Infante Linares JL, Tumin D. Projected estimates of African American medical graduates of closed historically Black medical schools. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2015220.

- Nelson A. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666-668.

- Scrimshaw SC, Backes EP, eds. Birth settings in America: Outcomes, quality, access, and choice. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2020. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25636.

- Rosenberg ES, Millett GA, Sullivan PS, Del Rio C, Curran JW. Understanding the HIV disparities between Black and White men who have sex with men in the USA using the HIV care continuum: a modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2014;1(3):e112-e118.

- Obesity, race/ethnicity, and COVID-19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/obesity-and-covid-19.html. Updated March 22, 2021. Accessed May 11, 2021.

- Ogden CL, Lamb MM, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Obesity and socioeconomic status in children and adolescents: United States, 2005-2008. NCHS Data Brief No. 51. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2010.

- Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS data brief, no 288. National Center for Health Statistics. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288.pdf

- Cozier YC, Yu J, Coogan PF, Bethea TN, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR. Racism, segregation, and risk of obesity in the Black women’s health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2014;179(7):875-883.

- Chow EA, Foster H, Gonzalez V, McIver L. The disparate impact of diabetes on racial/ethnic minority population. Clin Diab. 2012;30(3):130-133.

- Ludwig J, Sanbonmatsu L, Gennetian L, et al. Neighborhoods, obesity, and diabetes – A randomized social experiment. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1509-1519.

- Tung EL, Peek ME, Makelarski JA, Escamilla V, Lindau ST. Adult BMI and access to built environment resources in a high-poverty, urban geography. Am J Prev Med. 2016;51(5):e119-e127.

- Tung EL, Wroblewski KE, Boyd K, Makelarski JA, Peek ME, Lindau ST. Police-recorded crime and disparities in obesity and blood pressure status in Chicago. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e008030.

- Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm. Reviewed November 25, 2020. Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/maternal-mortality-ratio-(per-100-000-live-births). Accessed April 22, 2021.

- Green CR, Anderson KO, Baker TA, et al. The unequal burden of pain: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in pain. Pain Med. 2003;4(3):277-294.

- Green CR, Ndao-Brumblay SK, West B, Washington T. Differences in prescription opioid analgesic availability: comparing minority and White pharmacies across Michigan. J Pain. 2005;6(10):689-699.

- Bulgin D, Tanabe P, Jenerette C. Stigma of sickle cell disease: A systematic review. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(8):675-686.

- Adigweme O, Nelson CL, Watkins-Castillo SI. Ethnic and racial differences and disparities. United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS). 4th Rosemont, IL. 2020. http://www.boneandjointburden.org. Accessed on May 18, 2021.

- Ndao-Brumblay SK, Green CR. Predictors of complementary and alternative medicine use in chronic pain patients. Pain Med. 2010;11:16-24.

- Mackenzie ER, Taylor L, Bloom BS, Hufford DJ, Johnson JC. Ethnic minority use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): A national probability survey of CMA utilizers. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003;9(4):50-56.

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya, C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:1001–1006.

- Ghoshal M, Shapiro H, Todd K, Schatman ME. Chronic noncancer pain management and systemic racism: Time to move toward equal care standards. J Pain Res. 2020;13:2825.

- Meghani SH, Byun E, Gallagher RM. Time to take stock: a meta-analysis and systematic review of analgesic treatment disparities for pain in the United States. Pain Med. 2012;13(2):150-174.

- Hollingshead NA, Ashburn-Nardo L, Stewart JC, Hirsh AT. The pain experience of Hispanic Americans: a critical literature review and conceptual model. J Pain. 2016;17(5):513-528.

- Britton BV, Nagarajan N, Zogg CK, et al. US surgeons’ perceptions of racial/ethnic disparities in health care: A cross-sectional study. JAMA Surg. 2016;151(6):582-584.

- Diversity in medicine: Facts and figures 2019. Association of American Medical Colleges. aamc.org. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/report/diversity-medicine-facts-and-figures-2019. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- Current trends in medical education. AAMC. 2016. https://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures2016.org/report-section/section-3/.

- Distribution of allopathic medical school graduates by race/ethnicity. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. 2015. http://kff.org/other/state-indicator/distribution-by-race-ethnicity. Accessed May 10, 2021.

- Ezer N, Mhango G, Bagiella E, Goodman E, Flores R, Wisnivesky JP. Racial disparities in resection of early stage non–small cell lung cancer. Med Care. 2020;58(4), 392-398.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in premature deaths from heart disease, 2001. MMWR 53(6):121-125.

- Schulman KA, Berlin JA, Harless W, et al. The effect of race and sex on physicians’ recommendations for cardiac catheterization. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(8):618-626.

- Alkhouli M, Alqahtani F, Holmes DR, Berzingi C. Racial disparities in the utilization and outcomes of structural heart disease interventions in the United States. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(15):e012125.

- Rao S, Hughes AE, Ayers C, Das SR, Halm EA, Pandey A. Longitudinal trajectories and predictors of county-level cardiovascular mortality in the United States (1980-2014). 2021;143(Suppl_1):A076.

- Arya V, Butler K, Leal S, et al. Systemic racism: Pharmacists’ role and responsibility. Am J Pharm Ed. 2020;84(11):1453-1456.

- Grewal SK, Reddy V, Tomz A, Lester J, Linos E, Lee PK. Skin cancer in skin of color: A cross-sectional study investigating gaps in prevention campaigns on social media. J Am Acad Dermatol.

- Sanchez DP, Maymone MBC, McLean EO, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in melanoma awareness: A cross-sectional survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(4):1098-1103.

- Barbieri JS, Shin DB, Wang S, Margolis DJ, Takeshita J. Association of race/ethnicity and sex with differences in health care use and treatment for acne. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(3):312-319.

- Cancer stat facts: Melanoma of the skin. National Cancer Institute. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/melan.html. Accessed April 26, 2021.

- Melanoma of the skin statistics. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/skin/statistics/. Accessed April 26, 2021.

- Harvey VM, Oldfield CW, Chen JT, Eschbach K. Melanoma disparities among US Hispanics: Use of the social ecological model to contextualize reasons for inequitable outcomes and frame a research agenda. J Skin Cancer. 2016;2016:1-9.

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, Barnholtz-Sloan JS, Bordeaux JS. Racial disparities in melanoma survival. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(5):983–991.

- Harvey VM, Patel H, Sandhu S, Wallington SF, Hinds G. Social determinants of racial and ethnic disparities in cutaneous melanoma outcomes. Cancer Control. 2014;21(4):343-349.

- Fischer AH, Shin DB, Gelfand JM, Takeshita J. Health care utilization for psoriasis in the United States differs by race: An analysis of the 2001-2013 Medical Expenditure Panel surveys. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78(1):200-203.

- Kaufman BP, Alexis AF. Psoriasis in Skin of Color: Insights into the epidemiology, clinical presentation, genetics, quality-of-life impact, and treatment of psoriasis in non-White racial/ethnic groups. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;19(3):405–423.

- Louie P, Wilkes R. Representations of race and skin tone in medical textbook imagery. Soc Sci Med. 2018;202:38-42.

- Fenton A, Elliott E, Shahbandi A, et al. Medical students’ ability to diagnose common dermatologic conditions in skin of color. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):957-958.

- Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The health literacy of America’s adults: Results from the 2003 national assessment of adult literacy. National Center for Education Statistics. 2006. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2006/2006483.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2021.

- Northridge ME, Kumar A, Kaur R. Disparities in access to oral health care. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:513-535.

- Workforce. Health Policy Institute. American Dental Association. https://www.ada.org/en/science-research/health-policy-institute/dental-statistics/workforce. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disparities in oral health. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/oral_health_disparities/index.htm. Accessed April 29, 2021.

- Health Resources and Services Administration. Shortage areas: health professional shortage areas. Data.hrsa.gov. https://data.hrsa.gov/topics/health-workforce/shortage-areas. Updated August 17, 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021.

- Health Policy Institute. Racial and ethnic mix of the dentist workforce in the U.S. Ada.org. https://www.ada.org/~/media/ADA/Science%20and%20Research/HPI/Files/HPIgraphic_0421_1.pdf?la=en. Published February 2021. Accessed August 17, 2021.

- Hung H-C, Willett W, Merchant A, Rosner BA, Ascherio A, Joshipura KJ. Oral health and peripheral arterial disease. 2003;107(8):1152-1157.

- Dhadse P, Gattani D, Mishra R. The link between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease: How far we have come in last two decades? J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2010;14(3):148-154.

- Yenen Z, Ataçağ T. Oral care in pregnancy. J Turk Ger Gynocol Assoc. 2019;20(4):264-268.

- Kim SR, Schumaker E, Nichols M, Simon E. ‘Pharmacy deserts’ are new front in the race to vaccinate for COVID-19. Abcnews.com image https://abcnews.go.com/Health/pharmacy-deserts-front-race-vaccinate-covid-19/story?id=76201564. Published March 6, 2021. Accessed May 18, 2021.

- Qato DM, Daviglus ML, Wilder J, Lee T, Qato D, Lambert B. ‘Pharmacy deserts’ are prevalent in Chicago’s predominantly minority communities, raising medication access concerns. Health Aff. 2014;33(11):1958-1965.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National diabetes statistics report, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/diabetes/data/statistics-report/index.html. Accessed May 28, 2021.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services. Diabetes and African Americans. 2021. hhs.gov. https://www.minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=18. Accessed May 28, 2021.

- Pinto SL, Lively BT, Siganga W, Holiday‐Goodman M, Kamm G. Using the Health Belief Model to test factors affecting patient retention in diabetes‐related pharmaceutical care services. Res Social Adm Pharm2006;2:38-58.

- Joint Commission. Sentinel event data root causes by event type 2004-2014. 2014. Jointcommission.org. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/root_causes_by_event_type_2004-2014.pdf. Accessed May 28, 2021.

- Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. Errors in health care: a leading cause of death and injury. Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT, eds. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press (U.S.); 2000.

- Carbone E, Gorrie J, Oliver R. Without proper language interpretation, sight is lost in Oregon and a $350,000 verdict is reached. Legal Rev Commentary Suppl Healthcare Risk Manage. 2003;1.

- Lindholm N, Hargraves JL, Ferguson WJ, Reed G. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1294-1299.

- Liang BA. Limited English and health proficiency: A call for action to promote patient safety. J Patient Saf. 2007;3(2):57-60.

- Schenker Y, Wang F, Selig SJ, Ng R, Fernandez A. The impact of language barriers on documentation of informed consent at a hospital with on-site interpreter services. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(S2):294-299.

- Diamond LC, Schenker Y, Curry L, Bradley EH, Fernandez A. Getting by: underuse of interpreters by resident physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:256-262.

- Hoffman KM, Trawalter S, Axt JR, Oliver MN. Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between Blacks and Whites. PNAS. 2016;113(16):4296-4301.

- Morris DB, Gruppuso PA, McGee HA, Murillo AL, Grover A, Adashi EY. Diversity of the national medical student body – Four decades of inequities. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(17):1661-1668.

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89:817-827.

- Pandya AG Alexis AF, Berger TG, Wintroub BU. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity in dermatology: a call to action. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):584-587.

- McDade W, Vela MB, Sánchez JP. Anticipating the impact of the USMLE Step 1 pass/fail scoring decision on underrepresented-in-medicine students. Acad Med. 2020;95(9):1318-21.

- Phelan SM, Burke SE, Cunningham BA, et al. The effects of racism in medical education on students’ decisions to practice in underserved or minority communities. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1178-1189.

- Mateo CM, Williams DR. Addressing bias and reducing discrimination: The professional responsibility of health care providers. Acad Med. 2020;95(12S):S5-S10.

- Hu YY, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, abuse, harassment, and burnout in surgical residency training. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1741-1752.

- Victor RG, Blyler CA, Li N, et al. Sustainability of blood pressure reduction in Black barbershops. Circulation. 2019;139(1):10-19.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Chapter 2; Five health care sector activities to better integrate social care. In: Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: Moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. The National Academies Press; Washington DC. 2019. www.nap.edu. https://www.nap.edu/catalog/25467/integrating-social-care-into-the-delivery-of-health-care-moving.